Paradise Lost – The Green Lakes of Kanchenjunga

We are the pilgrims, master; we shall go

Always a little further: it may be

Beyond the last blue mountain barred with snow,

Across that angry or that glimmering sea

— James Elroy Flecker

I woke up that October morning in Gangtok with an indefinable sense of excitement. Slipping out of my bed at the Mintokling guest house, I paused before the heavy drawn curtains. Taking a deep breath, I pulled them quickly apart. A giant mountain appeared before my eyes, soaring like a white sail into the cloudless blue sky. For a few seconds, I could not recognise it from this unfamiliar sidelong view. And then the recognition and the memories came flooding back, filling my senses so quickly and completely, it was as if time had warped itself in that dark hotel room and I was a little boy once again.

Kanchenjunga. The very pronunciation of those four syllables sent a shiver down my spine and evoked memories buried deep in my childhood. Those pink-hued dawns when I watched spellbound from the window of my Dada and Dadi’s flat in Darjeeling as the rays of the rising sun lit up this most beautiful of mountains. An unforgettable spectacle, a vision so ephemeral as to be not of this earth, it floated like an enchanted castle in the crystal sky.

The musical name, Kanchenjunga translates as “The Five Treasures of the High Snows” in Sikkimese and mountaineers have kept the actual summit itself inviolate in respect of the feelings of the local people for whom the mountain is sacred. While the world knows it as the third highest mountain in the world (8,536m), it inspires tremendous awe and respect among Himalayan climbers as being more difficult and dangerous to climb than Everest. Also unlike Everest, which remains hidden behind its sister peaks hotse and Nuptse, this Himalayan giant absolutely dominates the skyline from a hundred miles away.

So when the call came from my friend Sujoy Das of South Col Expeditions that he was putting together a select group to visit the mythical Green Lakes nestled at the very base of the northeast face, there was absolutely no question in my mind that I would be in that number.

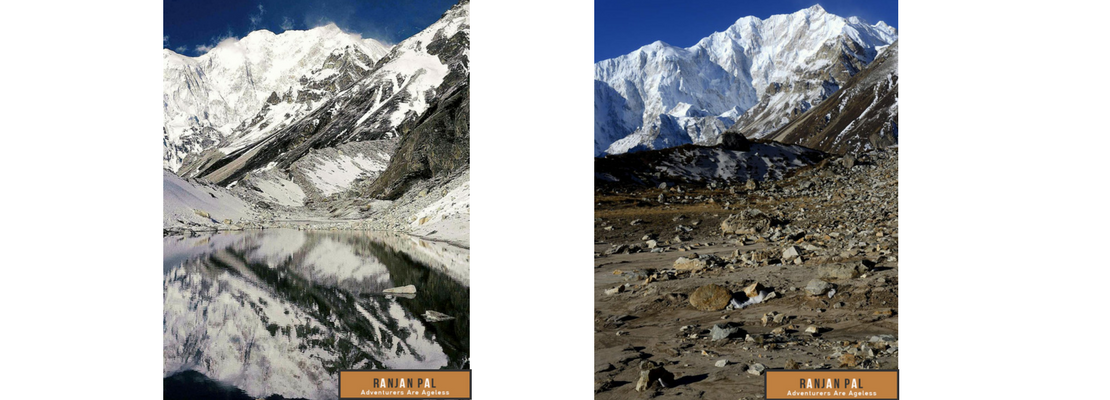

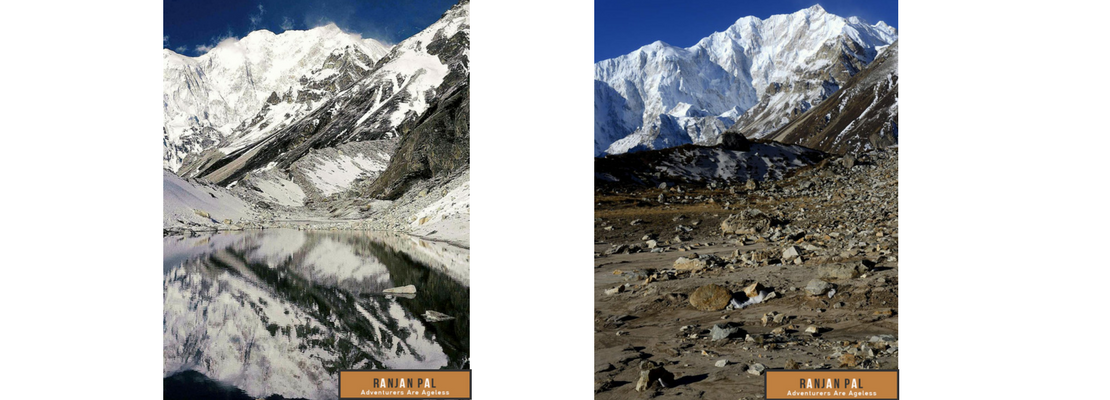

Our band of adventurers look happy at journey’s beginning

Sujoy himself was driven by a desire to return to Green Lakes, a magical place he had visited once before when he tagged along with the Assam Rifles Kanchenjunga expedition in 1987. Over 25 years had passed and the rumor was that global warming had wiped out the lakes forever. So he was very keen to retrace his steps and see if this disastrous scenario had in fact come true. For me an added attraction was how inaccessible (and hence pristine) the place was due to the multifarious permits one had to obtain to get there. Green Lakes fell in a “restricted travel” zone and the fact that Sujoy was the man who offered to navigate tortuous government channels to get the necessary permissions made it doubly attractive for the independent traveller.

As it turned out, we were to encounter the destructive nature of climate change on the very first day of our trek. Barely an hour after we had left the road head at Lachen following the right bank of the Zemu Chu, the river that drains the eastern ramparts of Kanchenjunga, the well-defined trail disappeared into sheer nothingness. We stared in dismay at the devastated landscape in front of us; the entire hillside had been wiped out by landslides for as far as the eye could see. Given that so few trekkers came this way every year, the local forest department did not see it as worthwhile to maintain the track which in turn discouraged further trekkers from coming — a real vicious circle!

The first day was a killer – the trail having been wiped out by landslides

For us there was no help for it but to forge ahead. And so hour after desperate hour, we struggled across the devastated landscape, falling and scraping ourselves on the grit and the scree. As I rested my aching limbs at our welcome night halt, I reflected dispiritedly on what nature had wrought in this once-beautiful valley. The process of glacial retreat had removed the firm ice support at the bottom of these hillsides — with nothing to hold them up, the slopes had simply washed away in the heavy monsoon.

The next day as we set out from Tallem under an overcast sky, the trail and the forests thankfully reappeared. Now the going was easier and we climbed steadily through lush forests of oak, magnolias and rhododendron, enjoying the thick silence of the morning. In two days we had not seen another soul other than our small group of seven trekkers and 20 support staff. We were truly all alone in this lost valley of the Zemu Chu as it plunged its way down from the Kanchenjunga massif.

I was to be reminded of our isolation in a most unpleasant way the very next morning. It’s funny how one small problem can escalate into a much bigger disaster; Murphy’s Law at work without a doubt. A freak spillage from my platypus had wet my sleeping bag which meant that I had to wait until it dried out. Consequently I started out alone, just a little behind the lead party but ahead of Sujoy and the porters bringing up the rear. Soon I found the well-defined trail climbing up the right bank of a stream that was tumbling down towards the Zemu Chu and followed it up, thinking I would soon come to the bridge.

An hour’s hard climb later, there was no sign of the bridge or of anyone either in front of or behind me on the trail. Worse still, the trail had now begun to bend away from the stream ! There was a sinking sensation in the pit of my stomach as I realised that I was well and truly lost in that lonely and deep valley. Trying to quell the panic that I felt rising in me, I called out for help repeatedly but the deep forest answered nothing back. It was a horrible feeling.

I decided that the best policy was to stay put in one place and wait. The minutes dragged by interminably and I was overwhelmed by emotions of utter loneliness and despair. Every now and then I stood up to call again and again but there was nothing. Finally I heard a distant answering whistle — I have never been so happy to hear a human sound in my life ! Soon I could see the bobbing head of Benod, our liaison officer moving rapidly up the trail below me. An adrenaline rush of relief replaced the panic — I was saved and it felt unimaginably good.

As we proceeded up the valley under the towering peaks of the Lama Ongdin range, more evidence of climate change became apparent. The rhododendron cover, which was confined to the proximity of the river bed when Sujoy first visited, had now spread its way up the mountain slopes as the weather had warmed. The Zemu glacier, which drains the east side of Kanchenjunga, had retreated 860 metres in the period 1909-2005 and the snout had moved much further upstream from its location in 1987 at our acclimatisation halt of Yabuk. Given its considerable length (26 km) and the heavy debris cover which insulates it from ablation, the extent of retreat has been relatively slow as glaciers in the Eastern Himalaya go.

North of Yabuk, the trail disappeared again into landslide debris but we became more eager and our pace quickened as glimpses of the great Himalayan giants could now be seen. I could sense their presence just beyond the top of the moraine. I felt like a privileged guest walking slowly through a giant foyer into the amphitheatre where the main show was about to begin. We were rewarded by the rare sight of a flock of bharal, the elusive blue Himalayan sheep as, surprised by our unexpected appearance, they scurried up the steep slopes to safety. I marvelled at the incredible agility of these beautiful creatures — only their natural predator, the mythical snow leopard could bring them down.

We finally reached our night halt of Rest Camp at 4,500 m right opposite the staggeringly beautiful Siniolchu (6,888m) described by Himalayan explorer Douglas Freshfield as the most “superb triumph of mountain architecture in the world.” First climbed by a team led by German mountaineer Paul Bauer in 1936, its fluted spires towered above us in the crystal sky. As my eye travelled right, I could see Little Siniolchu and the ice cream cake of Simvu and finally the magnificent spectacle of Kanchenjunga at the head of the valley.

The next morning we set out for our final destination of Green Lakes, following the alpine meadow on the right side of the giant Zemu glacier moraine. There was no trail anymore and we forded several minor streams of melt water as we wound our way upwards, the dry grass crunching under foot. It was getting windier and colder and the scudding clouds soon hid the mountain panorama. I wished I had worn my down jacket and warmer gloves as we struggled over the interminable plain which stretched away into the distance like the deck of a giant aircraft carrier.

Finally we could see the welcome splash of colour that signified our tents and the end of the line. Just beyond was the ugly mud flat which was all that remained of the magical Green Lakes. And above it another massive landslide had obliterated the route to the high viewing point which Sujoy had climbed up to in 1987. We scrambled up the side of the moraine which we have been following for the last two days and stared down at the spectacle far below. The Zemu glacier was a surreal sight with huge pools of green water speckled among a twisted landscape of ice and rock debris that stretched downwards as far as the eye could see. The river of ice had dropped 150 feet below its lateral moraines and several small glacial lakes had formed on its surface. It was an awesome though chilling reminder of the irreversible impact of climate change brought home in the most graphic way imaginable.

That night we celebrated the end of our journey with Indian whisky and Swiss chocolates! Very few people have been privileged to make this special pilgrimage to the very heart of the Kanchenjunga massif. In the light of the full moon with the glistening face of the great mountain soaring a vertical 3,000 m above us, we could so closely feel our utter solitude in this lost valley. All of us fell silent in a moment of prayer and gratitude.

**This article has originally appeared in the March 2016 edition of “Exotica” magazine. Check the PDF version here.

![]()

![]()